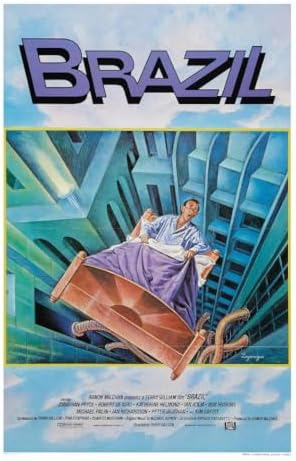

When Terry Gilliam named his 1985 dystopian satire Brazil, he wasn’t referring to the country. The title was inspired by the dreamy tones of “Aquarela do Brasil,” the iconic song by Ary Barroso, which haunts the film’s most surreal scenes. The Brazil that Gilliam envisioned was never meant to reflect any specific geography — and yet, 40 years later, it’s hard not to feel the eerie parallels between his absurdist nightmare and the state of the world today, Brazil included.

A Bureaucratic Hellscape With Familiar Shadows

Set in a not-so-distant future (or maybe an alternate present), Brazil introduces us to Sam Lowry, a low-level bureaucrat caught in the cogs of a colossal, indifferent government. It’s a world obsessed with forms, ducts, paperwork, and status — where the most horrifying crimes stem not from malice, but from clerical errors and a fanatical obedience to rules.

The film’s inciting moment — a smudged typewriter key leading to the wrongful arrest and death of an innocent man, Archibald Buttle — feels tragically plausible today. When Sam is tasked with delivering a refund check to Buttle’s grieving widow, the scene becomes one of the film’s most gut-wrenching. Her refusal to accept the check, and the quiet devastation of her presence, echoes with renewed resonance in a world where injustice often falls on those least equipped to defend themselves — from political prisoners to war refugees caught in the grip of bureaucracy.

The image of confused family members trying to navigate a justice system they barely understand feels eerily close to Gilliam’s vision: a state so invested in self-preservation that it ends up punishing precisely those it claims to serve — often sparing the very actors who set the machine in motion.

Cosmetic Escapism and a Culture of Denial

Sam’s mother, an emblem of the elite, undergoes grotesque beauty procedures in her desperate quest to remain youthful — a character detail that unintentionally mirrors Brazil’s real-world status as a global capital for plastic surgery. Her world is one of extravagant dinners, superficial facades, and indifference to the violence erupting — quite literally — behind her.

In one memorable dinner scene, a bomb explodes, and yet the wealthy patrons merely pause before resuming their foie gras. It’s a searing metaphor for a privileged class too insulated to react, a theme that transcends borders. It applies equally to rising class disparities, political apathy, and denialism in the face of violence or collapse.

Echoes of Orwell, With a Carnival Mask

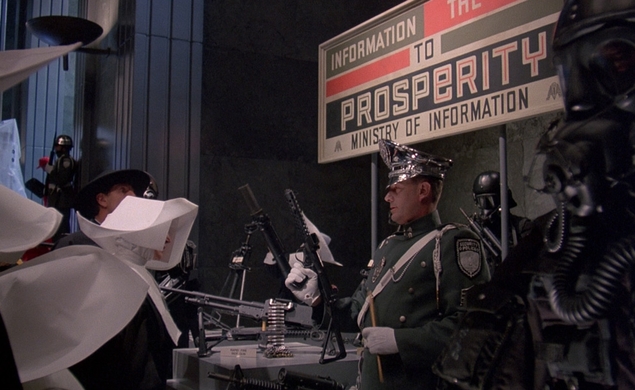

Often compared to 1984, Brazil builds on Orwellian themes with a twist. While 1984 imagines an oppressive world of thought control and totalitarian oversight, Brazil satirizes a different monster: the absurdity of bureaucracy. There’s no omnipotent Big Brother here — just endless forms, soulless managers, and a Ministry of Information that operates with no transparency, crushing people beneath the weight of propaganda.

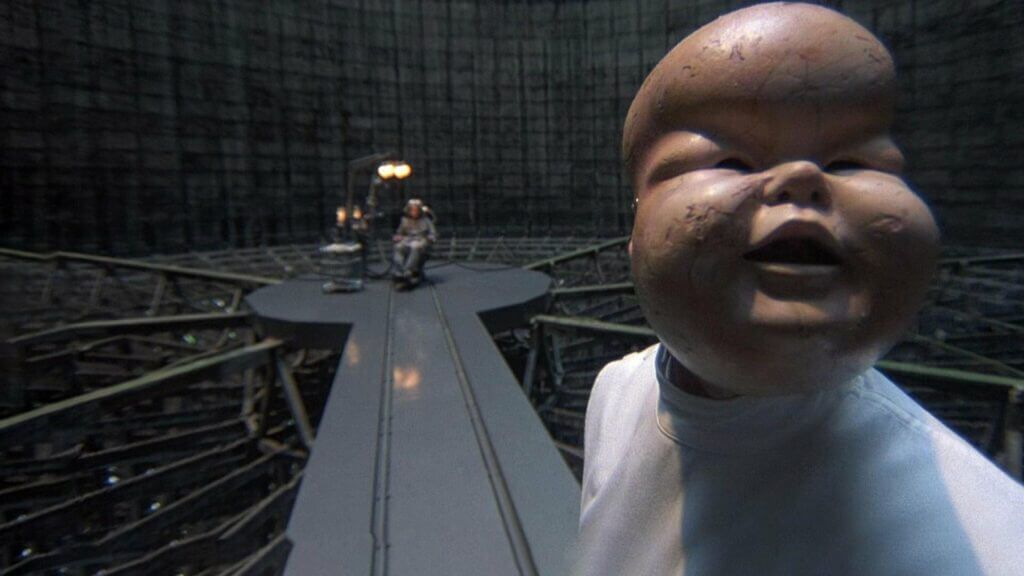

And yet, both protagonists — Winston Smith and Sam Lowry — follow the same tragic arc: disillusioned workers who dare to dream, fall in love, and are punished for it. But where 1984 is stark and relentless, Brazil wraps its horrors in slapstick, dreamscapes, and baroque visuals. It’s Orwell by way of Monty Python.

In one of the film’s surreal twists, Sam is ultimately strapped to a torture chair by his old friend Jack, played with eerie cheerfulness by Michael Palin. But help seems to arrive in the form of a rogue engineer, Archibald Tuttle — portrayed by Robert De Niro in one of his most unconventional roles. Tuttle, a renegade air-conditioning repairman, becomes a folk hero in Sam’s mind: a symbol of resistance, freedom, and just maybe, sanity. But like everything in Brazil, his rescue may only exist in Sam’s fantasies.

Fascism With a Smile

Perhaps the most terrifying thing about Brazil is that no one really seems evil. They’re just doing their jobs. From baby-faced torturers to bombed-out bureaucrats, everyone plays their part in a society that rewards obedience and punishes compassion. Even Sam, our reluctant hero, begins the story aloof and complicit — it’s only through love, guilt, and madness that he begins to see the machine for what it is.

Gilliam’s portrayal of fascism is not militarized in the traditional sense. It’s consumerist, cosmetic, bureaucratic. It arrests you for bad paperwork. It values your credit score over your life. It suggests that the true horror of authoritarianism may not come from jackboots, but from endless forms stamped in triplicate.

If that sounds familiar, it should. Across the world, from Brasília to Washington D.C., the symptoms are easy to spot: political polarization, surveillance disguised as security, misinformation wrapped in national colors, and a growing trust in those who promise to fix the complexities of human behavior.

The “Brazil” That Lives In All of Us

And yet, Brazil isn’t about Brazil. The country’s name appears only in the song that underscores Sam’s dreams — escapist moments of freedom and love that float above the concrete wreckage of his world. That’s the real irony: the film’s most joyful moments happen when Brazil — the idea — plays in the background. A fantasy of tropical beauty and liberation that lives only in Sam’s subconscious.

But that dream isn’t entirely abstract. For those who know Brazil — or simply long to wake up to a summer morning there — the country’s warmth, sensuality, and spirit of joyful escape seem to seep into the film’s atmosphere, like a memory just out of reach.

In that sense, Brazil is not about a place, but about the universal human instinct to dream amid despair. To resist, even if only in imagination. To believe in beauty, even when reality becomes absurd. That dream, like Barroso’s song, is seductive. And perhaps, even necessary.

So happy birthday, Brazil. You weren’t about us — but somehow, you became about everyone.