In an inspiring journey that bridges her Brazilian roots with her medical studies in the United States, Beatriz de Faria Sousa, a second-year medical student at Florida International University, recently embarked on an extraordinary adventure. Born in São Paulo and now based in Miami, Beatriz’s passion for understanding human nature and her relentless curiosity have always driven her to explore beyond the conventional. This summer, her quest for deeper knowledge led her and her friend, Adriana Oliveira, a law student from Rio, to the remote Pataxó indigenous tribe in Bahia, Brazil.

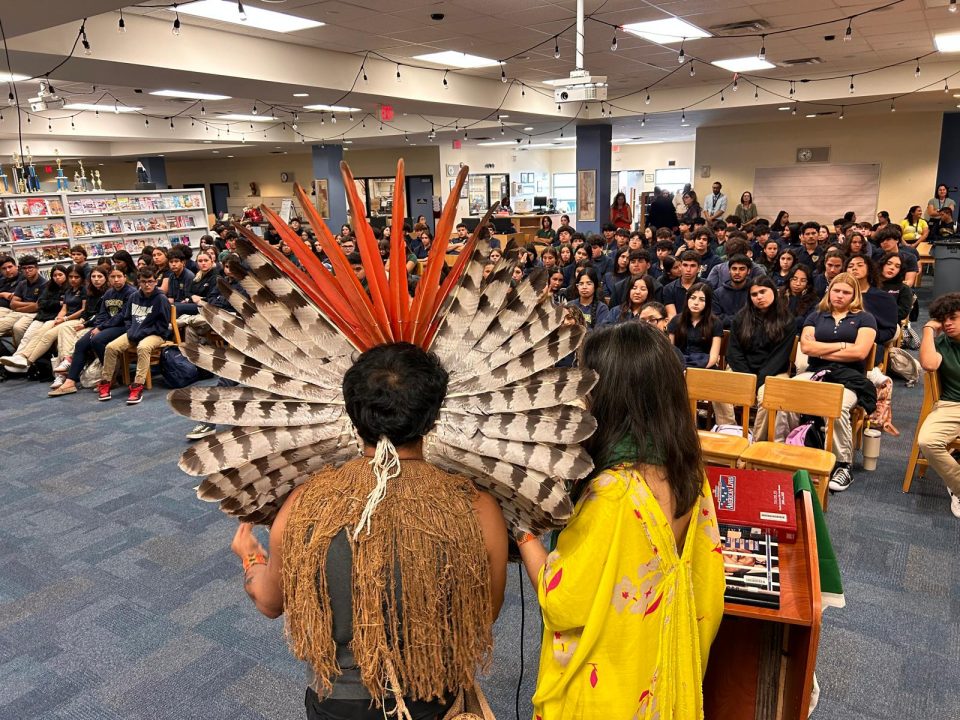

Their host was Arassari, chief of the Pataxó tribe, who has become a well-known figure among students in Florida due to his impactful lectures across schools and universities in the state. Over the past few years, Arassari has visited institutions such as Ada Merritt, Downtown Doral Charter Upper School, Ronald Reagan Senior High School, and the University of Miami, celebrating Indigenous Peoples’ Day, observed on April 19 in Brazil.

Supported by the Consulate-General of Brazil in Miami, Arassari’s presentations not only delve into Brazil’s history from the indigenous perspective but also foster discussions about forest conservation and indigenous lifestyles. Dressed in traditional attire, Arassari shares insights about his people’s origins and the significant role of the Pataxós as the first indigenous group to encounter Pedro Álvares Cabral’s caravels in Porto Seguro. With a background in law, Arassari travels extensively throughout Brazil, educating about the approximately 20,000 Pataxós living in Bahia, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro.

Arassari’s efforts to improve conditions for his people, including advocating for agricultural support and basic food supplies, highlighted a pressing need for development. During her stay, Beatriz said in an interview for Brazilcore that she was struck by the contrast between the Pataxós’ traditional practices and their modern struggles. She was surprised to find that, despite having ample land, the tribe relied heavily on government-provided food baskets and faced hardships when supplies were insufficient.

In this interview, Beatriz reflects on her transformative experience, offering a unique glimpse into the life of the Pataxó tribe and the valuable insights she gained from this profound cultural exchange.

Immersive Experience with the Pataxó Tribe

“My name is Beatriz de Faria Sousa, and I am a second-year medical student at Florida International University. I was born in São Paulo, Brazil, and moved to the United States when I was 17 because my father was transferred from his job at Citibank.

One of my attributes that led me to medicine was my intense curiosity and deep desire to learn, especially about the nature of humankind. I want to become my best version to help others do the same. Those are the same motives that led me to do most of the things in my life, including spending 4 days at an indigenous tribe in Bahia, Brazil, during my summer break.

In his junior year of high school, my brother helped create a club called PRA (Portuguese Remedial Association), which focused on promoting Portuguese and Brazilian culture. Together with the Brazilian Consulate, he organized a lecture with Arassari, the chief of the Pataxó tribe, who would come to teach about his culture in South Florida. Arassari met my mother and brother and grew fond of them; he invited both to visit his tribe in Brazil. As they couldn’t go, my family suggested I go to their place. So, I did.

I first met Arassari Pataxó at the Porto Seguro airport. I saw a man dressed like all others but wearing typical indigenous bracelets, earrings, and necklaces. He was very nice, greeted my friend and I, and took us to his car. I was surprised he had a car. Then I was astounded at my astonishment with the fact he had a car. I noticed how little I knew about indigenous tribes and how prejudiced I was. I had a lot to learn.

During the 4-hour car ride to his tribe, Arassari indulged us in his culture and beliefs—the beliefs of his tribe, the Pataxó. I learned so much during those 4 hours, not only about their medicine but also their culture and values. Arassari started telling us that he had some doctors visit his tribe wanting to study and understand why there aren’t any children born with Down Syndrome and neurological problems in indigenous tribes. Arassari thinks it is because of the intense care for the mother’s health during pregnancy. The tribe makes sure the future mother rests, drinks tea, does not get stressed, receives massages, attention, and is sung to. The future mother is respected and taken care of. Childbirth and labor are fundamental moments, in which the mother must squat down for the delivery of the child. Arassari tells us there is a lot of prejudice around it; people say that when this happens in the tribe, it is something only “savages” do, but when the same thing happens in “fancy” hospitals, it is called “humanized childbirth”.

Arassari then told us about child development. According to the Pataxó tribe, children have “five senses of learning.” They start with smell; they are used to the smell of their family and cry when they sense foreign smells. The second one is taste, the phase in which the child wants to put everything in their mouth, and the third phase is touch, in which the child breaks things and touches to learn. The fourth is hearing, and the last one is sight. Arassari says the “white man,” as he calls non-indigenous people, sits children in chairs and makes them stay in school and learn how to read and write before they are ready. He does not believe there is such a thing as ADHD or anxiety at this age. He thinks it is just the “white man” not respecting the “principle” of child development.

Concerning medicine, Arassari tells us his tribe tries to be as natural as possible. Most illnesses are treated with teas made from different plants. If the issue is not resolved, their last resort is ayahuasca, which he says is their strongest medicine. He compares it to our antibiotics. It “disconnects you from reality, from the world.” You cannot talk, you vomit, and you have diarrhea. The body needs to clean and repurify itself. The ayahuasca tea is made with a specific herb, chacruna, which is smashed and made into tea. It also allows you to talk to your ancestors, which is very important to indigenous tribes, who believe the elderly are the wisest. According to Arassari, when you talk to your ancestors, they allow you to come back calmer, as you work out your problems and come back with a weight off your shoulders.

Ayahuasca holds deep cultural and spiritual significance for many Indigenous tribes, including the Pataxó. It is not merely a recreational substance, but a sacred medicine used during times of hardship, whether for spiritual healing or physical ailments. For these communities, the casual use of ayahuasca by outsiders, who often seek it out for its hallucinogenic effects, can be deeply offensive. It trivializes something that is meant to be approached with respect and intention. The tribes feel frustrated by this commercialization, as ayahuasca is not meant for entertainment—it’s a profound, healing tool meant to address genuine struggles.

Arassari also mentions the importance of authenticity. To them, medicine makes you be yourself. Ayahuasca allows you to search for who you are. Some diseases are “social diseases”—society, friends, and family’s behavior can sometimes lead you to make decisions that make you sick or depressed, with neurological problems. Those are the “spiritual illnesses.”

Besides ayahuasca, other herbs used include “rapé”, an important herb put into one’s nose and then blown out. This medication is used for depression, emotional problems, and “things society makes you believe are absolute truths.”

Arassari says depression is trauma the unconscious cannot solve. It is a “social disease” present in all regions of the world. He mentioned there was only one girl in his village who had it, but she was cured with rapé and ayahuasca. Ayahuasca allows one to see inside, to search for their mission. He believes there is not a lot of depression in indigenous tribes because they believe we are not in the world for nothing. We are here on a mission, and we need to find it. If one takes time to find it or needs to change their mission, they do not get frustrated; they allow themselves to resignify their lives without remorse. Change pathways because maybe the previous one was not their true mission. One must have focus, attention, and concentration. And try hard. According to Arassari, indigenous people know how to manage frustration because they are used to fighting for their survival, constantly learning, and being attentive to their surroundings.

In addition to treating diseases, indigenous people place a lot of effort in prevention. They drink tea every day, do rituals, and sing songs to “feed” their spirit, to allow them to be healthy, and to prevent them from needing any treatment at all. As a neuroscience enthusiast and someone who believes in prevention as the best medicine, I was in awe.

In the Pataxó tribe, I spent four days sleeping in a hammock, with no electricity, no hot showers, and no cell phone connection. Nonetheless, I got to see the focus on the collective and how close-knit his family was. I got to play with the children, telling stories and hearing theirs. We went canoeing, and I helped build a clay house. I saw their appreciation for their grandparents, respect for them, and genuine interest in hearing their stories. I participated in rituals, singing, and dancing, learning their dialect. I was amused at how much the children enjoyed those and how involved they were. I experienced their appreciation for nature and how much they know about all kinds of fruits, birds, seeds, and plants. I climbed Monte Pascoal, the mountain that Pedro Álvares Cabral first saw, mistakenly assuming he had arrived in India. I saw all the Mata Atlântica from up there—magnificent, stunning, majestic—and also the unfortunate action of the “white man” on nature, as there were multiple farms in deforested areas nearby.

I also got to see the impact of the “white man” on Arassari’s village. While drawing with the children, they would make me M&M cakes. Some of them had phones and played video games, even with no signal or internet. Arassari’s mother had diabetes and took insulin shots, and his father wore hearing aids.

While I saw in the tribe much of what Arassari told me about their lifestyle, I also noticed the presence of multiple cultural factors from my own culture. Indeed, there were teas and rituals, but there were also insulin and hearing aids. There was lots of storytelling but sometimes cellphones.

I understand why Arassari wants to protect the village and his heritage. I think it is very important. As a lawyer and teacher, Arassari recognizes the usefulness of having a cell phone and a car. He is extremely knowledgeable, inventive, and smart. Nonetheless, he wants to keep the “white man’s influence” to a minimum. But while he sees the mixture of cultures as something adverse, I find it positive. I find it amazing that they can keep their traditions while incorporating some important things from the “white man’s world,” like insulin. I believe both cultures have so much to offer. And while they benefit from ours, we would also benefit from theirs. That is why I decided to write this testimony. I believe it is fundamental that we also focus more on prevention, healthy lifestyles, understanding children’s development, and acknowledging our surroundings—the “social and spiritual diseases.” We need to understand and respect nature and others, work on understanding and respecting ourselves, focus on the collective, and do so without losing our authenticity. We should strive to become our best versions to help others do the same.”

For those interested in experiencing an immersion like Beatriz’s in the Pataxó village, you can contact Arassari through Instagram @arassari_pataxo

View this post on Instagram